One of the most frequent questions an operating company asks in the context of a merger with a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) is, "When must management of the new company report on its internal controls over financial reporting (ICFR)?" The answer, not surprisingly, is ..."It depends!"

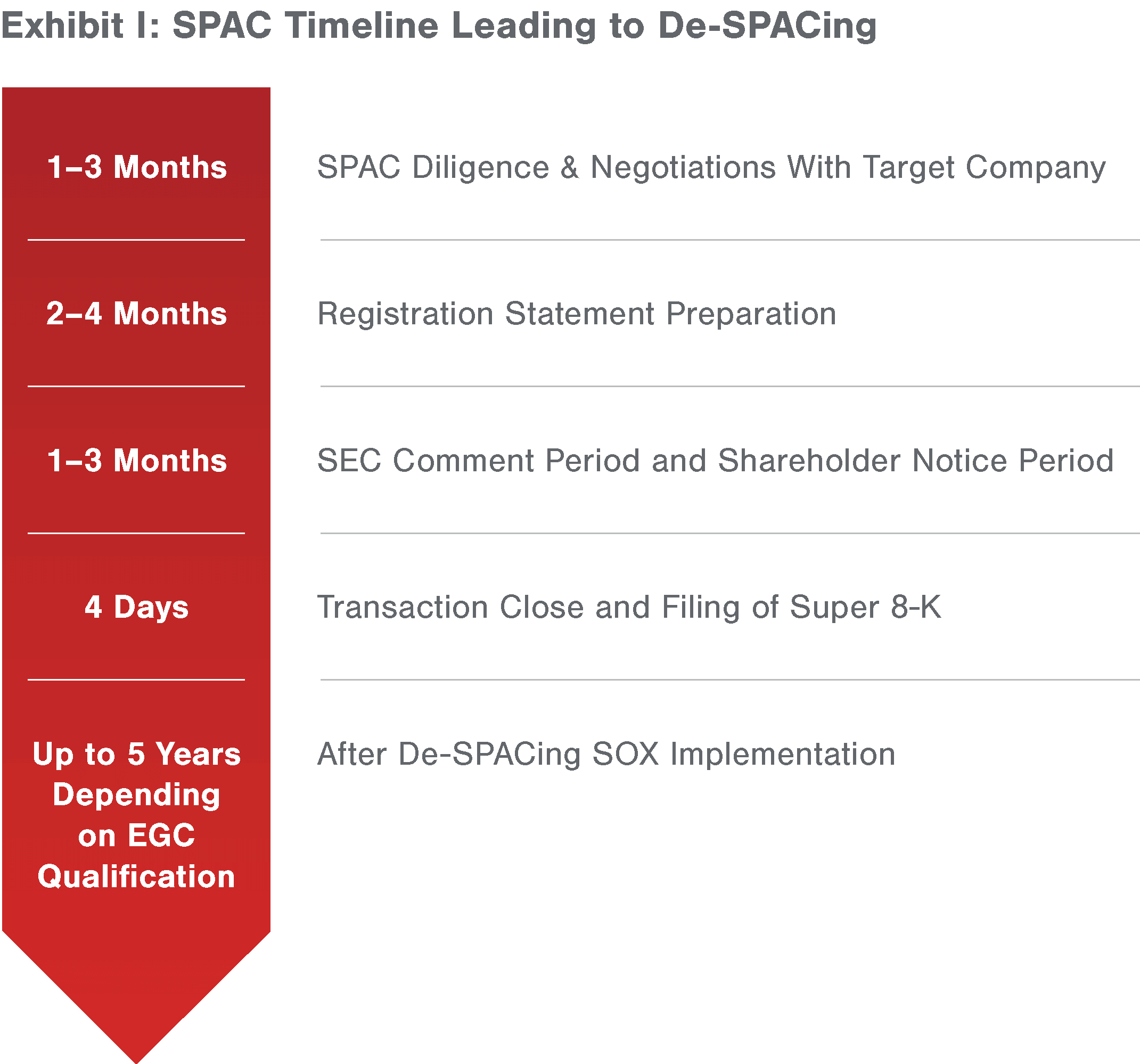

A Typical SPAC Timeline

A SPAC is a public company that has been organized, registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and raised funds from the public with the intention of ultimately acquiring an operating company. The SPAC has no substantive operations, and its only focus is to invest its funds within a specified time period. A SPAC will typically look at many operating company target candidates before it chooses the entity in which it has interest and that fits its expressed investment objectives. Most SPACs must deploy shareholder funds within a pre-determined life span, generally not more than two years. If the life span expires before the SPAC can invest its funds, it must return those funds to its shareholders. Accordingly, there is some pressure on the SPAC to invest in a timely manner.

Once a suitable target has been identified, the SPAC will enter negotiations with the operating company's management, likely the founders of the private company. Although these discussions may progress quite quickly, it is more often the case that these negotiations can take two to three months. Once a transaction has been agreed upon in concept by the parties, several more months may pass of additional due diligence and preparation before the transaction is finalized. The primary activity that takes time is the preparation of the registration statement, including the preparation and auditing of the target's required financial statements, and related SEC filings, such as proxy statements for the acquiring shareholders to vote on the transaction.

Once an initial registration statement has been filed, the SEC staff will review the filing and provide comments that must be cleared before the registration statement can become effective. Once the registration statement is declared effective, the deal can be consummated, and the SPAC acquires the operating company in what is referred to as a "de-SPACing" transaction. While the complexity of the accounting is not our focus here, the transaction is often accounted for as a "reverse merger," in which the operating company is viewed as the acquirer of the SPAC for accounting purposes. At that point, the newly combined company must file a Form 8-K (often referred to as a "Super 8-K" due to the extensive nature of its content) no later than four days after the closing of the transaction to remain in compliance with the securities laws.

The Complexity of Requirements for Reporting on Internal Controls Over Financial Reporting

The purpose in describing the timing of this process is to illustrate that putting together a successful transaction takes time, in some cases more than a year from the time the SPAC filed its initial registration statement with the SEC. A critical path in that process is the preparation of financial statements in compliance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) and related SEC reporting requirements.

The preparation of accurate GAAP financial statements is highly dependent on a company maintaining strong ICFR. That was the driving force behind elements of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, specifically Section 404 of the Act (often referred to as SOX 404), which requires a report from management on the adequacy of its ICFR as well as, most likely at some point in the future, a report from the registrant's auditors. Thus, that frequent question … when does that reporting requirement begin?

Management of a new public company is not required to report on ICFR until it is filing its second annual report on Form 10-K. But does that apply to the "new" public company formed by a SPAC?

Hint: The New Operating Company's Super 8-K Filing Date Matters

Relevant interpretive guidance by the SEC can be found in the staff's Compliance & Disclosure Interpretations related to Regulation S-K in Section 215.02, which states the following in part:

"The guidance provided in Management's Report on Internal Control Over Financial Reporting and Certification of Disclosure in Exchange Act Periodic Reports, Frequently Asked Questions No. 3 does not relate to reverse acquisitions between an issuer and a private operating company, and the surviving issuer in a reverse acquisition is not a "newly public company" as that term is used in Exchange Act Release No. 54942 (Dec. 15, 2006). However, the staff acknowledges that it might not always be possible to conduct an assessment of the private operating company or accounting acquirer's internal control over financial reporting in the period between the consummation date of a reverse acquisition and the date of management's assessment of internal control over financial reporting required by Item 308(a) of Regulation S-K. We also recognize that in many of these transactions, such as those in which the legal acquirer is a non-operating public shell company, the internal controls of the legal acquirer may no longer exist as of the assessment date or the assets, liabilities, and operations may be insignificant when compared to the consolidated entity. In the instances described above, the staff would not object if the surviving issuer were to exclude management's assessment of internal control over financial reporting in the Form 10-K covering the fiscal year in which the transaction was consummated. However, when the transaction is consummated shortly after year-end and surviving issuer is required to file an amended Form 8-K to update its financial statements for its most recent year-end, that filing is equivalent to the first annual report subsequent to the consummation of the transaction and future annual reports should not exclude management's report on internal control over financial reporting. Similar conclusions may also be reached in transactions involving special-purpose acquisition companies."

Said a little more plainly, the usual relief from immediately reporting on management's assessment of the ICFR for a new public company does not apply to a shell company acquisition of an operating company, i.e., a typical SPAC transaction. However, the SEC recognizes that the internal controls of the SPAC acquiror may no longer exist, having been supplanted by those of the company with the real operations, and that the previously privately owned operating company may not yet have appropriate controls in place. As a result, the SEC may not object to management of the combined company omitting its assessment of ICFR in the next annual Form 10-K. However, it should be noted that if the deal is transacted and the "Super 8-K" is filed shortly after a year-end, the Form 8-K is effectively the same as the combined company's "next" Form 10-K. Therefore, depending upon the filing date of the Super 8-K, the company could potentially have to report on its ICFR assessment in the first true Form 10-K filing following the transaction, which could be a few weeks away.

Example: A Super 8-K Filing Date's Impact on Management's Timing of ICFR

If the de-SPACing transaction closes on January 1, 20X2, and the "Super 8-K" is filed four days later, which would include financial statements for 20X0, then that would be the "next" Form 10-K. When the Form 10-K is filed for 20X1 likely in March, it would require management's report in ICFR. Regardless, if circumstances do allow management to omit its report on ICFR, and if management chooses to do so, then management must still disclose why such an assessment has not been included, addressing the effect of the transaction on management's ability to conduct an assessment.

Other ICFR Timing Factors to Consider

The final shoe to drop on ICFR reporting relates to when the company's auditor will begin to be required to issue its own report on internal control. The size of the company and its filing status as a "Smaller Reporting Company," "Accelerated Filer," or an "Emerging Growth Company" will help determine that.

A company considering going public via a merger with a SPAC must consider all the facts and circumstances in determining when it must be prepared to report on management's assessment of the ICFR in its annual Form 10-K. There are many factors that can influence the correct response, and a company should consult with its auditors and legal counsel. To summarize, the answer to the common question of "When does the newly combined, newly public company (SPAC and acquired operating company) need to report on ICFR?" … "It depends!"

For questions or more information, reach out to your FORVIS professional, or fill out the Contact Us form below.